Richard's October Update

Oct 31, 2020Asio Coroutines in Qt applications!

I started this train of thought when I wanted to hook up some back-end style code that I had written to a gui front end. One way to do this would be to have a web front end subscribing to a back-end service, but I am no expert in modern web technologies so rather than spend time learning something that wasn’t C++ I decided to reach for the popular-but-so-far-unused-by-me C++ GUI framework, Qt.

The challenge was how to hook up Qt, which is an event driven framework to a service written with Asio C++ coroutines.

In the end it turned out to be easier than I had expected. Here’s how.

A simple Executor

As mentioned in a previous blog, Asio comes with a full implementation of the Unified Executors proposal. Asio coroutines are designed to be initiated and continued within an executor’s execution context. So let’s build an executor that will perform work in a Qt UI thread.

The executor I am going to build will have to invoke completion handlers to Asio IO objects, so we need to make it

compatible with asio::any_io_executor. This means it needs to have an associated

execution context.

The execution context is going to ultimately perform work on a Qt Application, so it makes sense to capture a reference

to the Application. Although Qt defines the macro qApp to resolve to a pointer to the “current” application, for

testing and sanity purposes I prefer that all services I write allow dependency injection, so I’ll arrange things so

that the execution_context’s constructor takes an optional pointer to an application. In addition, it will be convenient

when writing components to not have to specifically create and pass an an execution context to windows within the Qt

application so it makes sense to be able to provide access to a default context which references the default application.

Here’s a first cut:

struct qt_execution_context : net::execution_context

, boost::noncopyable

{

qt_execution_context(QApplication *app = qApp)

: app_(app)

{

instance_ = this;

}

template<class F>

void

post(F f)

{

// todo

}

static qt_execution_context &

singleton()

{

assert(instance_);

return *instance_;

}

private:

static qt_execution_context *instance_;

QApplication *app_;

};

This class will provide two services. The first is to provide the asio service infrastructure so that we can create

timers, sockets etc that use executors associated with this context and the second is to allow the executor to actually

dispatch work in a Qt application. This is the purpose of the post method.

Now a Qt application is itself a kind of execution context - in that it dispatches QEvent objects to be handled by children of the application. We can use this infrastructure to ensure that work dispatched by this execution context actually takes place on the correct thread and at the correct time.

In order for us to dispatch work to the application, we need to wrap our function into a QEvent:

class qt_work_event_base : public QEvent

{

public:

qt_work_event_base()

: QEvent(generated_type())

{

}

virtual void

invoke() = 0;

static QEvent::Type

generated_type()

{

static int event_type = QEvent::registerEventType();

return static_cast<QEvent::Type>(event_type);

}

};

template<class F>

struct basic_qt_work_event : qt_work_event_base

{

basic_qt_work_event(F f)

: f_(std::move(f))

{}

void

invoke() override

{

f_();

}

private:

F f_;

};

As opposed to using a std::function, the basic_qt_work_event allows us to wrap a move-only function object, which is

important when that object is actually an Asio completion handler. Completion handlers benefit from being move-only as

it means they can carry move-only state. This makes them more versatile, and can often lead to improvements in

execution performance.

Now we just need to fill out the code for qt_execution_context::post and provide a mechanism in the Qt application to

detect and dispatch these messages:

template<class F>

void

post(F f)

{

// c++20 auto template deduction

auto event = new basic_qt_work_event(std::move(f));

QApplication::postEvent(app_, event);

}

class qt_net_application : public QApplication

{

using QApplication::QApplication;

protected:

bool

event(QEvent *event) override;

};

bool

qt_net_application::event(QEvent *event)

{

if (event->type() == qt_work_event_base::generated_type())

{

auto p = static_cast<qt_work_event_base*>(event);

p->accept();

p->invoke();

return true;

}

else

{

return QApplication::event(event);

}

}

Note that I have seen on stack overflow the technique of invoking a function object in the destructor of the

QEvent-derived event. This would mean no necessity of custom event handling in the QApplication but there are two

problems that I can see with this approach:

- I don’t know enough about Qt to know that this is safe and correct, and

- Executors-TS executors can be destroyed while there are still un-invoked handlers within them. The correct behaviour is to destroy these handlers without invoking them. If we put invocation code in the destructors, they will actually mass-invoke when the executor is destroyed, leading most probably to annihilation of our program by segfault.

However, that being done, we can now write the executor to meet the minimal expectations of an asio executor which can

be used in an any_io_executor.

struct qt_executor

{

qt_executor(qt_execution_context &context = qt_execution_context::singleton()) noexcept

: context_(std::addressof(context))

{

}

qt_execution_context &query(net::execution::context_t) const noexcept

{

return *context_;

}

static constexpr net::execution::blocking_t

query(net::execution::blocking_t) noexcept

{

return net::execution::blocking.never;

}

static constexpr net::execution::relationship_t

query(net::execution::relationship_t) noexcept

{

return net::execution::relationship.fork;

}

static constexpr net::execution::outstanding_work_t

query(net::execution::outstanding_work_t) noexcept

{

return net::execution::outstanding_work.tracked;

}

template < typename OtherAllocator >

static constexpr auto query(

net::execution::allocator_t< OtherAllocator >) noexcept

{

return std::allocator<void>();

}

static constexpr auto

query(net::execution::allocator_t< void >) noexcept

{

return std::allocator<void>();

}

template<class F>

void

execute(F f) const

{

context_->post(std::move(f));

}

bool

operator==(qt_executor const &other) const noexcept

{

return context_ == other.context_;

}

bool

operator!=(qt_executor const &other) const noexcept

{

return !(*this == other);

}

private:

qt_execution_context *context_;

};

static_assert(net::execution::is_executor_v<qt_executor>);

Now all that remains is to write a subclass of some Qt Widget so that we can dispatch some work against it.

class test_widget : public QTextEdit

{

Q_OBJECT

public:

using QTextEdit::QTextEdit;

private:

void

showEvent(QShowEvent *event) override;

void

hideEvent(QHideEvent *event) override;

net::awaitable<void>

run_demo();

};

void

test_widget::showEvent(QShowEvent *event)

{

net::co_spawn(

qt_executor(), [this] {

return run_demo();

},

net::detached);

QTextEdit::showEvent(event);

}

void

test_widget::hideEvent(QHideEvent *event)

{

QWidget::hideEvent(event);

}

net::awaitable<void>

test_widget::run_demo()

{

using namespace std::literals;

auto timer = net::high_resolution_timer(co_await net::this_coro::executor);

for (int i = 0; i < 10; ++i)

{

timer.expires_after(1s);

co_await timer.async_wait(net::use_awaitable);

this->setText(QString::fromStdString(std::to_string(i + 1) + " seconds"));

}

co_return;

}

Here is the code for stage 1

And here is a screenshot of the app running:

All very well…

OK, so we have a coroutine running in a Qt application. This is nice because it allows us to express an event-driven system in terms of procedural expression of code in a coroutine.

But what if the user closes the window before the coroutine completes?

This application has created the window on the stack, but in a larger application, there will be multiple windows and they may open and close at any time. It is not unusual in Qt to delete a closed window. If the coroutine continues to run once the windows that’s hosting it is deleted, we are sure to get a segfault.

One answer to this is to maintain a sentinel in the Qt widget implementation, which prevents the continuation of the

coroutine if destroyed. A std::shared_ptr/weak_ptr pair would seem like a sensible solution. Let’s create an updated

version of the executor:

struct qt_guarded_executor

{

qt_guarded_executor(std::weak_ptr<void> guard,

qt_execution_context &context

= qt_execution_context::singleton()) noexcept

: context_(std::addressof(context))

, guard_(std::move(guard))

{}

qt_execution_context &query(net::execution::context_t) const noexcept

{

return *context_;

}

static constexpr net::execution::blocking_t

query(net::execution::blocking_t) noexcept

{

return net::execution::blocking.never;

}

static constexpr net::execution::relationship_t

query(net::execution::relationship_t) noexcept

{

return net::execution::relationship.fork;

}

static constexpr net::execution::outstanding_work_t

query(net::execution::outstanding_work_t) noexcept

{

return net::execution::outstanding_work.tracked;

}

template<typename OtherAllocator>

static constexpr auto

query(net::execution::allocator_t<OtherAllocator>) noexcept

{

return std::allocator<void>();

}

static constexpr auto query(net::execution::allocator_t<void>) noexcept

{

return std::allocator<void>();

}

template<class F>

void

execute(F f) const

{

if (auto lock1 = guard_.lock())

{

context_->post([guard = guard_, f = std::move(f)]() mutable {

if (auto lock2 = guard.lock())

f();

});

}

}

bool

operator==(qt_guarded_executor const &other) const noexcept

{

return context_ == other.context_ && !guard_.owner_before(other.guard_)

&& !other.guard_.owner_before(guard_);

}

bool

operator!=(qt_guarded_executor const &other) const noexcept

{

return !(*this == other);

}

private:

qt_execution_context *context_;

std::weak_ptr<void> guard_;

};

Now we’ll make a little boilerplate class that we can use as a base class in any executor-enabled object in Qt:

struct has_guarded_executor

{

using executor_type = qt_guarded_executor;

has_guarded_executor(qt_execution_context &ctx

= qt_execution_context::singleton())

: context_(std::addressof(ctx))

{

new_guard();

}

void

new_guard()

{

static int x = 0;

guard_ = std::shared_ptr<int>(std::addressof(x),

// no-op deleter

[](auto *) {});

}

void

reset_guard()

{

guard_.reset();

}

executor_type

get_executor() const

{

return qt_guarded_executor(guard_, *context_);

}

private:

qt_execution_context *context_;

std::shared_ptr<void> guard_;

};

And we can modify the test_widget to use it:

class test_widget

: public QTextEdit

, public has_guarded_executor

{

...

};

void

test_widget::showEvent(QShowEvent *event)

{

// stop all existing coroutines and create a new guard

new_guard();

// start our coroutine

net::co_spawn(

get_executor(), [this] { return run_demo(); }, net::detached);

QTextEdit::showEvent(event);

}

void

test_widget::hideEvent(QHideEvent *event)

{

// stop all coroutines

reset_guard();

QWidget::hideEvent(event);

}

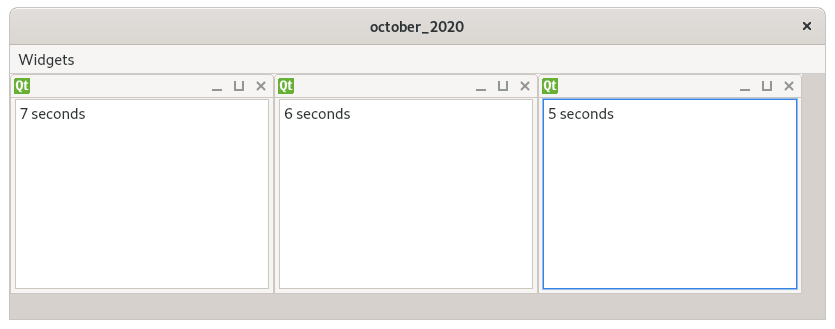

Now we’ll update the application to allow the creation and deletion of our widget. For this I’ll use the QMdiWindow and add a menu with an action to create new widgets.

We are now able to create and destroy widgets at will, with no segfaults.

If you look at the code, you’ll also see that I’ve wired up a rudimentary signal/slot device to allow the coroutine to be cancelled early.

// test_widget.hpp

void

listen_for_stop(std::function<void()> slot);

void

stop_all();

std::vector<std::function<void()>> stop_signals_;

bool stopped_ = false;

// test_widget.cpp

void

test_widget::listen_for_stop(std::function<void()> slot)

{

if (stopped_)

return slot();

stop_signals_.push_back(std::move(slot));

}

void

test_widget::stop_all()

{

stopped_ = true;

auto copy = std::exchange(stop_signals_, {});

for (auto &slot : copy) slot();

}

void

test_widget::closeEvent(QCloseEvent *event)

{

stop_all();

QWidget::closeEvent(event);

}

net::awaitable<void>

test_widget::run_demo()

{

using namespace std::literals;

auto timer = net::high_resolution_timer(co_await net::this_coro::executor);

auto done = false;

listen_for_stop([&] {

done = true;

timer.cancel();

});

while (!done)

{

for (int i = 0; i < 10; ++i)

{

timer.expires_after(1s);

auto ec = boost::system::error_code();

co_await timer.async_wait(

net::redirect_error(net::use_awaitable, ec));

if (ec)

{

done = true;

break;

}

this->setText(

QString::fromStdString(std::to_string(i + 1) + " seconds"));

}

for (int i = 10; i--;)

{

timer.expires_after(250ms);

auto ec = boost::system::error_code();

co_await timer.async_wait(

net::redirect_error(net::use_awaitable, ec));

if (ec)

{

done = true;

break;

}

this->setText(QString::fromStdString(std::to_string(i)));

}

}

co_return;

}

Apparently I am told that it’s been a long-believed myth that Asio “doesn’t do cancellation”. This is of course, nonsense.

Here’s the code for stage 2

State of the Art

It’s worth mentioning that I wrote and tested this demo using clang-9 and the libc++ version of the standard library. I have also successfully tested clang-11 with coroutines (and concepts). As I understand it, recent versions of Visual Studio support both well. GCC 10 - although advertising support for coroutines - has given me trouble, exhibiting segfaults at run time.

Apple Clang, of course, is as always well behind the curve with no support for coroutines. If you want to try this code on a mac, it’s entirely possible as long as you ditch the Apple compiler and use the homebrew’s clang:

brew install llvm

Clang will then be available in /usr/local/opt/bin and you will need to set your CMAKE_CXX_COMPILER CMake variable

appropriately. For completeness, it’s worth mentioning that I also installed Qt5 using homebrew. You will need to

set Qt5_DIR. Something like this:

cmake -H. -Bmy_build_dir -DCMAKE_CXX_COMPILER=/usr/local/opt/llvm/clang++ -DQt5_DIR=/usr/local/opt/qt5/lib/cmake/Qt5

Going further

Ok, so what if we want our Qt application to interact with some asio-based service running in another thread?

For this I’m going to create a few boilerplate classes. The reason is that we’re going to have multiple threads running and each thread is going to be executing multiple coroutines. Each coroutine has an associated executor and that executor is dispatching completion handlers (which for our purposes advance the progress of the coroutines) in one of the threads assigned to it.

It is important that coroutines are able to synchronise with each other, similar to the way that threads synchronise with each other.

In fact, it’s reasonable to use the mental model that a coroutine is a kind of “thread”.

In standard C++, we have the class std::condition_variable which we can wait on for some condition to be fulfilled.

If we were to produce a similar class for coroutines, then coroutines could co_await on each other. This could form the

basis of an asynchronous event queue.

First the condition_variable, implemented in terms of cancellation of an Asio timer to indicate readiness (thanks to Chris Kohlhoff - the author of Asio - for suggesting this and saving me having reach for another library or worse, write my own awaitable type!):

struct async_condition_variable

{

private:

using timer_type = net::high_resolution_timer;

public:

using clock_type = timer_type::clock_type;

using duration = timer_type::duration;

using time_point = timer_type::time_point;

using executor_type = timer_type::executor_type;

/// Constructor

/// @param exec is the executor to associate with the internal timer.

explicit inline async_condition_variable(net::any_io_executor exec);

template<class Pred>

[[nodiscard]]

auto

wait(Pred pred) -> net::awaitable<void>;

template<class Pred>

[[nodiscard]]

auto

wait_until(Pred pred, time_point limit) -> net::awaitable<std::cv_status>;

template<class Pred>

[[nodiscard]]

auto

wait_for(Pred pred, duration d) -> net::awaitable<std::cv_status>;

auto

get_executor() noexcept -> executor_type

{

return timer_.get_executor();

}

inline void

notify_one();

inline void

notify_all();

/// Put the condition into a stop state so that all future awaits fail.

inline void

stop();

auto

error() const -> error_code const &

{

return error_;

}

void

reset()

{

error_ = {};

}

private:

timer_type timer_;

error_code error_;

std::multiset<timer_type::time_point> wait_times_;

};

template<class Pred>

auto

async_condition_variable::wait_until(Pred pred, time_point limit)

-> net::awaitable<std::cv_status>

{

assert(co_await net::this_coro::executor == timer_.get_executor());

while (not error_ and not pred())

{

if (auto now = clock_type::now(); now >= limit)

co_return std::cv_status::timeout;

// insert our expiry time into the set and remember where it is

auto where = wait_times_.insert(limit);

// find the nearest expiry time and set the timeout for that one

auto when = *wait_times_.begin();

if (timer_.expiry() != when)

timer_.expires_at(when);

// wait for timeout or cancellation

error_code ec;

co_await timer_.async_wait(net::redirect_error(net::use_awaitable, ec));

// remove our expiry time from the set

wait_times_.erase(where);

// any error other than operation_aborted is unexpected

if (ec and ec != net::error::operation_aborted)

if (not error_)

error_ = ec;

}

if (error_)

throw system_error(error_);

co_return std::cv_status::no_timeout;

}

template<class Pred>

auto

async_condition_variable::wait(Pred pred) -> net::awaitable<void>

{

auto stat = co_await wait_until(std::move(pred), time_point::max());

boost::ignore_unused(stat);

co_return;

}

template<class Pred>

auto

async_condition_variable::wait_for(Pred pred, duration d)

-> net::awaitable<std::cv_status>

{

return wait_until(std::move(pred), clock_type::now() + d);

}

async_condition_variable::async_condition_variable(net::any_io_executor exec)

: timer_(std::move(exec))

, error_()

{}

void

async_condition_variable::notify_one()

{

timer_.cancel_one();

}

void

async_condition_variable::notify_all()

{

timer_.cancel();

}

void

async_condition_variable::stop()

{

error_ = net::error::operation_aborted;

notify_all();

}

For our purposes this one is a little too all-singing and all-dancing as it allows for timed waits from multiple

coroutines. This is not needed in our example, but I happened to have the code handy from previous experiments.

You will notice that I have marked the coroutines as [[nodiscard]]. This is to ensure that I don’t forget to

co_await them at the call site. I can’t tell you how many times I have done that and then wondered why my program

mysteriously freezes mid run.

Having built the condition_variable, we now need some kind of waitable queue. I have implemented this in terms of some

shared state which contains an async_condition_variable and some kind of queue. I have made the implementation of the

queue a template function (another over-complication for our purposes). The template represents the strategy for

accumulating messages before they have been consumed by the client. The strategy I have used here is a FIFO, which means

that every message posted will be consumed in the order in which they were posted. But it could just as easily be a

priority queue, or a latch - i.e. only storing the most recent message.

The code to describe this machinery is a little long to put inline, but by all means look at the code:

The next piece of machinery we need is the actual service that will be delivering messages. The code is more-or-less a copy/paste of the code that was in our widget because it’s doing the same job - delivering messages, but this time via the basic_distributor.

Note that the message_service class is a pimpl. Although it uses a shared_ptr to hold the impl’s lifetime, it is itself non-copyable. When the message_service is destroyed, it will signal its impl to stop. The impl will last a little longer than the handle, while it shuts itself down.

The main coroutine on the impl is called run() and it is initiated when the impl is created:

message_service::message_service(const executor_type &exec)

: exec_(exec)

, impl_(std::make_shared<message_service_impl>(exec_))

{

net::co_spawn(

impl_->get_executor(),

[impl = impl_]() -> net::awaitable<void> { co_await impl->run(); },

net::detached);

}

Note that the impl shared_ptr has been captured in the lambda. Normally we’d need to be careful here because the

lambda is just a class who’s operator() happens to be a coroutine. This means that the actual coroutine can outlive the

lambda that initiated it, which means that impl could be destroyed before the coroutine finishes. For this reason

it’s generally safer to pass the impl to the coroutine as an argument, so that it gets decay_copied into the

coroutine state.

However, in this case we’re safe. net::co_spawn will actually copy the lambda object before invoking it, guaranteeing

- with asio at least - that the impl will survive the execution of the coroutine.

And here’s the run() coroutine:

net::awaitable<void>

message_service_impl::run()

{

using namespace std::literals;

auto timer

= net::high_resolution_timer(co_await net::this_coro::executor);

auto done = false;

listen_for_stop([&] {

done = true;

timer.cancel();

});

while (!done)

{

for (int i = 0; i < 10 && !done; ++i)

{

timer.expires_after(1s);

auto ec = boost::system::error_code();

co_await timer.async_wait(

net::redirect_error(net::use_awaitable, ec));

if (ec)

break;

message_dist_.notify_value(std::to_string(i + 1) + " seconds");

}

for (int i = 10; i-- && !done;)

{

timer.expires_after(250ms);

auto ec = boost::system::error_code();

co_await timer.async_wait(

net::redirect_error(net::use_awaitable, ec));

if (ec)

break;

message_dist_.notify_value(std::to_string(i));

}

}

}

Notice the done machinery allowing detection of a stop event. Remember that a stop event can arrive at any time. The

first this coroutine will hear of it is when one of the timer async_wait calls is canceled. Note that the lambda

passed to listen_for_stop is not actually part of the coroutine. It is a separate function that just happens to

refer to the same state that the coroutine refers to. The communication between the two is via the timer cancellation

and the done flag. This communication is guaranteed not to race because both the coroutine and the lambda are executed

by the same strand.

Finally we need to modify the widget:

net::awaitable<void>

test_widget::run_demo()

{

using namespace std::literals;

auto service = message_service(ioexec_);

auto conn = co_await service.connect();

auto done = false;

listen_for_stop([&] {

done = true;

conn.disconnect();

service.reset();

});

while (!done)

{

auto message = co_await conn.consume();

this->setText(QString::fromStdString(message));

}

co_return;

}

This coroutine will exit via exception when the distributor feeding the connection is destroyed. This will happen when the impl of the service is destroyed.

Here is the final code for stage 3.

I’ve covered quite a few topics here and I hope this has been useful and interesting for people interested in exploring coroutines and the think-async mindset.

There are a number of things I have not covered, the most important of which is improving the (currently very basic)

qt_guarded_executor to improve its performance. At the present time, whether you call dispatch or post referencing

this executor type, a post will actually be performed. Perhaps next month I’ll revisit and add the extra machinery to

allow net::dispatch(e, f) to offer straight-through execution if we’re already on the correct Qt thread.

If you have any questions or suggestions I’m happy to hear them. You can generally find me in the #beast channel

on cpplang slack or if you prefer you can either email me

or create an issue on this repo.

All Posts by This Author

- 08/10/2022 Richard's August Update

- 10/10/2021 Richard's October Update

- 05/30/2021 Richard's May 2021 Update

- 04/30/2021 Richard's April Update

- 03/30/2021 Richard's February/March Update

- 01/31/2021 Richard's January Update

- 01/01/2021 Richard's New Year Update - Reusable HTTP Connections

- 12/22/2020 Richard's November/December Update

- 10/31/2020 Richard's October Update

- 09/30/2020 Richard's September Update

- 09/01/2020 Richard's August Update

- 08/01/2020 Richard's July Update

- 07/01/2020 Richard's May/June Update

- 04/30/2020 Richard's April Update

- 03/31/2020 Richard's March Update

- 02/29/2020 Richard's February Update

- 01/31/2020 Richard's January Update

- View All Posts...